When Culture Meets Crisis: How Son Preference Mitigated Gender Inequality During China’s Great Famine

This article discusses the findings of an Asian Development Bank study on how social norms, particularly son preference, influenced gender inequality during the Great Chinese Famine of 1959–1961. The study reveals that in regions with a strong cultural preference for sons, the negative impact of the famine on male survival rates and gender inequality in health and education was mitigated.

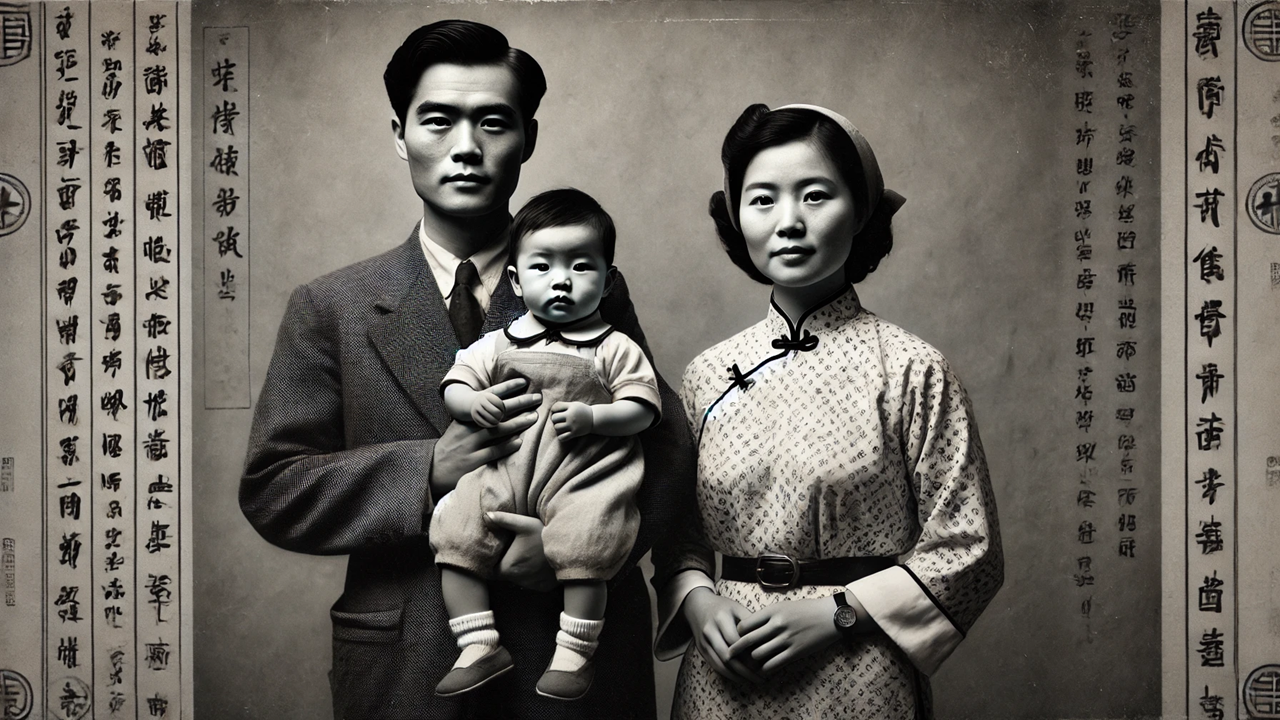

In the late 1950s, China faced one of the deadliest famines in human history. The Great Chinese Famine of 1959–1961, driven by a combination of political mismanagement and natural disasters, left deep scars on the nation. Yet, as devastating as this period was, the way it shaped gender inequality provides a crucial lesson in the interplay between social norms and survival. A recent study by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) explores how cultural preferences, particularly the traditional son preference, influenced the survival chances and future opportunities of males and females during this catastrophic event.

The Great Famine: A National Tragedy

The Great Chinese Famine stands as one of the darkest chapters in China’s modern history. During these years, agricultural production plummeted, leading to widespread starvation. The famine’s death toll remains a matter of debate, but it is widely accepted that millions perished. However, the impact of this famine extended beyond the immediate loss of life—it shaped the trajectory of those who survived, particularly through the lens of gender inequality.

Researchers Wei Luo, Wei Huang, and Albert Park, in their ADB working paper, examined how exposure to the affected gender inequality in health and education. Using data from the 2000 Population Census of the People’s Republic of China, the study reveals that social norms—specifically the cultural preference for sons—played a significant role in mitigating some of the famine’s harshest impacts on gender inequality.

Son Preference and Survival

In many parts of China, especially during the mid-20th century, sons were traditionally valued more than daughters. This preference is deeply rooted in cultural beliefs that sons carry on the family name and provide for parents in old age. The ADB study shows that this cultural norm had a profound impact during the famine.

The researchers found that in regions with strong son preference, the negative effects of famine on male survival rates were less severe. This suggests that families may have allocated scarce resources preferentially to sons, enhancing their chances of survival. As a result, while the famine generally reduced the male-to-female sex ratio, this reduction was less pronounced in areas where son preference was stronger. This cultural buffering effect meant that in regions with a strong preference for sons, the gender inequality in health and education caused by the famine was less severe than in other regions.

Long-Term Consequences for Gender Inequality

The study also highlights the long-term consequences of this interaction between social norms and adverse shocks. In regions where son preference was strong, not only were male survival rates higher, but the gender gap in education was also narrower. This suggests that the preferential treatment of sons during the famine extended beyond survival, influencing educational opportunities and long-term human capital investments.

However, this does not imply that son preference eliminated gender inequality. Instead, it underscores the complex ways in which cultural norms can shape the impact of crises. In gender-neutral regions, the famine exacerbated gender disparities, with girls suffering more significant disadvantages in health and education. In contrast, in regions with a strong preference for sons, these disparities were somewhat mitigated, though not entirely erased.

Implications for Policy and Future Research

The findings of the ADB study have significant implications for policy, particularly in regions where cultural preferences still influence gender dynamics. As the world continues to face challenges such as pandemics, economic crises, and climate change, understanding the role of social norms in shaping gender inequality becomes increasingly important. Targeted interventions that address gender-specific vulnerabilities are crucial, especially in societies with strong cultural preferences.

The study also opens avenues for further research into how cultural context interacts with adverse events to shape gender outcomes. By considering these cultural factors, policymakers and researchers can better anticipate and address the long-term impacts of crises on gender inequality.

The Great Chinese Famine was a tragedy of unimaginable proportions, but its impact on gender inequality offers critical insights into the interplay between culture and crisis. As this ADB study demonstrates, social norms like son preference can significantly influence survival and long-term opportunities, underscoring the need for culturally informed policies in addressing gender disparities. In the face of future challenges, these lessons from history remind us of the importance of understanding and addressing the deep-rooted cultural factors that shape human resilience and inequality.

- FIRST PUBLISHED IN:

- Devdiscourse

ALSO READ

China: UN rights office reiterates need to review national security framework

US Open to Discuss Philippine Ship Escorts Amid South China Sea Tensions

Market Slump: Disappointing Interim Results Impact China and Hong Kong Stocks

Pacific Leaders Endorse AU$400M Police Training Plan to Counter China

Foreign-Branded Smartphone Sales Surge in China