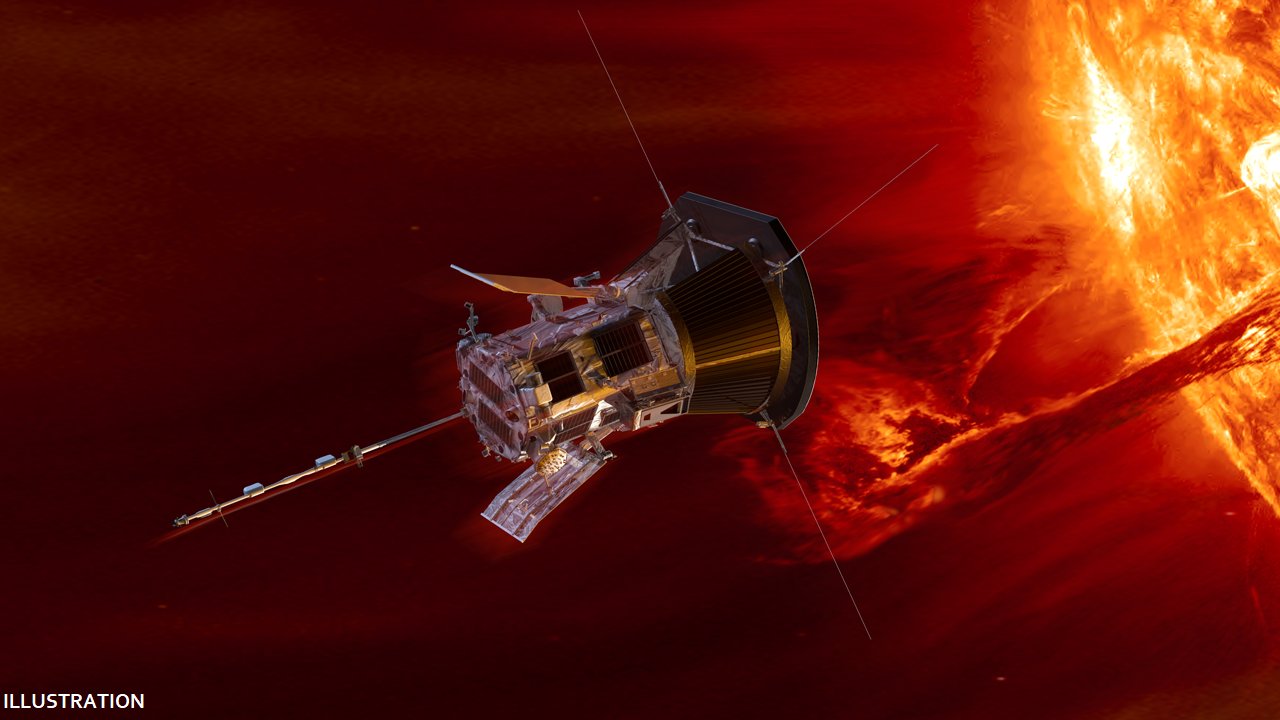

NASA's Parker Solar Probe turns 4; sending back more than twice the planned amount of science data

NASA's Parker Solar Probe launched on a historic mission to study the Sun up close on August 12, 2018. Now four years after launch, the spacecraft is operating exceptionally well and sending back more than twice the planned amount of science data, the agency said on Friday.

"Despite operating in such an extreme environment, Parker is performing well beyond our expectations. The spacecraft and its payload are making spectacular observations that will revolutionize our understanding of the Sun and the heliosphere, and that is a testament to the innovation and tireless dedication of the team," said Helene Winters, Parker Solar Probe project manager at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland.

As #ParkerSolarProbe orbits around the Sun, it operates in extreme environments and experiences temperatures of 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit (800 degrees Celsius).Parker helps scientists better understand our Sun and its effect on our solar system.https://t.co/3b1msduxjH pic.twitter.com/XXH0VgvHRm

— NASA Sun & Space (@NASASun) August 12, 2022

NASA's Parker Solar Probe continues to break records and capture first-of-its-kind measurements of the Sun. In December 2021, the spacecraft achieved its cornerstone objective - making the first measurements from within the atmosphere of a star.

According to NASA, Parker has sent back roughly 2.8 terabytes of scientific data, approximately equivalent to the amount of data in 200 hours of 4K video, in its four years of operation. Next month, the spacecraft will complete its 13th perihelion, its closest approach to the Sun in this orbit, of 24 planned for Parker's primary mission.

During that encounter, Parker will fly through the Sun's upper atmosphere, the corona, for the sixth time. The spacecraft's closest pass of the Sun is planned to occur in 2024, when it will come within 4 million miles (6.2 million kilometers) of the solar surface at speeds topping 430,000 miles per hour.

"We're looking forward to the rest of the mission, and that closest perihelion at the end of the primary mission," said Jim Kinnison, the Parker Solar Probe mission systems engineer at APL.