SPECIAL REPORT-Arab fighters killed boys and men in war on Sudan tribe, mothers allege

But the men continued beating him until he lay dead. Abdel Karim was one of more than 40 mothers who described to Reuters how their children, mostly boys, were killed by Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitary and its allied Arab militias during an ethnically targeted killing campaign this year in and around the West Darfur capital of El Geneina.

The Arab militiamen were hunting for boys that day. That’s how they found 2-year-old Ibrahim Saleh.

Ibrahim, his baby sister and their mother, Safaa Abdel Karim, were on the run in June, fleeing a weeks-long massacre in the Sudanese city of El Geneina. Arab militiamen had shot, stabbed and burned to death members of their tribe, the darker-skinned Masalit people. Abdel Karim’s husband was among the dead. Along with dozens of women and children, she and her kids were trying to make it to safety in neighboring Chad. They almost did.

About 10 kilometers from the border, she said, Arab paramilitary forces and militiamen stopped them and ordered her to hand over Ibrahim. They looked inside his clothes to inspect his sex, then set him down and began bashing his head and body with wooden rods. “He was crying, mama, mama,” Abdel Karim said. When she tried to rescue him, one of the men shot her below the shoulder, she said, leaving a scar from the wound. “I kept screaming to leave my son. Don’t kill my son.”

The men kept striking Ibrahim. “You zurga won’t stay in El Geneina,” the men shouted, using a racist term for darker-skinned people like the Masalit. “They said if the boy grows up, he will fight us.” Bleeding from her wound and with her daughter in her arms, Abdel Karim said she kept trying to stop the attack on Ibrahim. But the men continued beating him until he lay dead.

Abdel Karim was one of more than 40 mothers who described to Reuters how their children, mostly boys, were killed by Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitary and its allied Arab militias during an ethnically targeted killing campaign this year in and around the West Darfur capital of El Geneina. Her son and the other children were all part of the Masalit tribe, which was a majority in El Geneina until the RSF and Arab militias forced them out. Around half a million people, mostly Masalit, have left for Chad as a result of the violence.

Thousands have died in the attacks. The dead include women and girls. Masalit women also have described enduring sexual assault at the hands of the Arab-dominated RSF and its allies, as Reuters detailed last month. But in the killing sprees, witnesses say, Arab forces have specifically targeted males for death, from infants to adults.

Thirty-six of the mothers told Reuters their children were shot from close range, 33 of them boys and eight girls. Six of the mothers said they watched as their children, some as young as six months old, were beaten to death by RSF and Arab militia fighters. Five of the six children killed this way were boys. The killers used knives, too: Ten people who escaped to Chad told Reuters they saw children having their throats slit. All were boys.

Most of these children were killed as they fled with their mothers from El Geneina. En route to Chad, five survivors described seeing militiamen stop women with babies, check the child’s sex, and kill it if it turned out to be a boy. Masalit men were also hunted down by the RSF and its allies. In the most recent round of violence in El Geneina in early November, Reuters revealed that hundreds of young Masalit men were rounded up and taken to various locations in the city where eyewitnesses said some of them were executed.

More than 30 women interviewed for this report said their husbands, brothers or fathers were killed or went missing in this year’s attacks. Several women said they hid their brothers or smuggled them out of El Geneina for fear they would be targeted. Dozens of men recounted how they cut through valleys and traveled along remote routes to Chad to evade checkpoints set up by the RSF and Arab militias. Reuters was unable to independently corroborate the details of some accounts. In some cases, friends and neighbors confirmed elements of the survivors’ stories. Common patterns also emerged from the descriptions of the violence given by survivors. For some people, Reuters was able to review registration cards issued for refugees by the United Nations.

U.N. workers in Chad have so far collected demographic data on more than a quarter of the 484,000 refugees who have fled Sudan this year and now reside in camps along the border. Based on this data, the U.N. estimates nearly twice as many adult females as males have crossed the border. Despite the targeting of males, the gap is less pronounced among children, where there is almost parity between the number of boys and girls. Several mothers of slain children, as well as other witnesses, said the militiamen made clear why they were targeting Masalit boys: They wanted to be sure the children wouldn’t grow up to be fighters and one day seek revenge for the attacks on the Masalit.

Aziza Adam Mohammed, 28, said her six-month-old son was shot and killed on June 14 as they fled to Chad with a group of other refugees. When Arab militiamen confronted the group, she said, “They shouted: Shoot, shoot the boys.” “I heard them saying that the boys will grow up and they will kill us,” she said. “So we must destroy them now.”

Ana Scattone, an emergency protection officer at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in the Chadian border town of Adre, said the targeting of males also has a more far-reaching goal. “The objective of the killings seems to be the elimination of future fighters as well as the line of ancestry of a specific ethnic group,” Scattone said. Masoud Mohammed Youssef, the coordinator of an umbrella group that represents some of the Arab tribes in El Geneina, said the Masalit are “fabricating” stories to sway public opinion. The accusation that Arab militias and the RSF targeted male Masalit children and adults was “baseless,” he said.

The only Masalit who “were killed in the fighting in El Geneina,” he added, were armed fighters. “The rest of society, they lived,” he said. Arab tribal leaders have previously blamed the Masalit for instigating the violence. The RSF didn't respond to questions from Reuters. In prior statements, the paramilitary has said it wasn't involved in what it called a tribal conflict in El Geneina.

The war against the Masalit erupted amid a broader conflict between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the RSF, partners in a 2021 coup that crushed hopes for a transition to democracy in Sudan. They began battling in the capital Khartoum in April, after splitting over how to apportion power in a proposed shift toward civilian rule. In early December, the United States determined that both the RSF and the Sudanese army have committed war crimes since fighting broke out and spread to Darfur. Secretary of State Antony Blinken said the RSF, which draws its forces largely from Arab groups, and its allied militias have also committed crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing. Both the army and the RSF have blamed each other for any abuses committed in the war.

CLUBBED TO DEATH Abdullah Omar Abdullah, a Sudanese army soldier, said he was on the run with a group of 16 other Masalit men in early November. They were heading by car through the mountains west of El Geneina toward Chad. Abdullah had just escaped his army base in Ardamata, a district on the outskirts of El Geneina. The base had been overrun by RSF forces as the paramilitary consolidated its hold on the city.

As the group made its way through the mountains, RSF and Arab militia forces ambushed them and opened fire. Abdullah was struck in the hand by a bullet and flung from the car. Clutching the wound to stop the bleeding, he slid into a ditch as he tried to evade the attackers. Abdullah began to shake visibly as he described what he saw next from his hideout.

Uniformed RSF forces and Arab militiamen were stopping Masalit women on the same route who were heading for Chad with babies on their backs. The militiamen aimed their guns at the mothers and ordered them to hand over the children. The gunmen then opened the babies’ clothes to check their sex. “If they found it was a boy, they shot them right away,” said Abdullah. “The babies were so small, so small.”

Abdullah said he saw three babies killed in this way. “I couldn’t do anything,” he said, as tears began to roll down his cheeks.

“What I have seen is terribly sad,” he added. Then he covered his face with his hands and walked away. Four other people who fled to Chad also told Reuters they saw RSF forces and Arab militiamen undressing babies to check their sex.

Maymouna Abbakr, 25, and her 9-month-old daughter narrowly escaped with their lives twice as they fled El Geneina on June 15. First, she said, they were surrounded by a group of knife-wielding Arab militiamen. The men forced Abbakr to take her baby off her back, then removed the child’s clothes. “It’s a girl,” Abbakr recalls screaming. She snatched her baby back, and the men allowed her to go. A few kilometers later, she was stopped again by armed men, and her baby was checked once more.

In an effort to save their sons, some mothers dressed them in women’s clothes. When Awatef Adam, a 43-year-old mother of seven, fled to Chad in mid-June, she hedged her bets. Adam said she left one son and three daughters with relatives and neighbors in the city, while she headed to Chad with another son and two daughters. She hoped this would ensure that at least some of her children survived.

Knowing Arab militiamen were targeting Masalit males, for the journey to Chad she dressed her 12-year-old son Fayez in a head scarf and a black abaya, the full-length robe worn by some Muslim women. For part of the journey the ruse worked. Fayez passed undetected through several checkpoints manned by RSF and Arab militia forces. But when they got to Shukri, a village about 10 kilometers from the Chad border, their luck ran out. Adam said five men – two in RSF uniforms and three in traditional robes – spotted Fayez and surrounded him.

“Slaves, this is our land,” they shouted. “Get out.” Then they lifted Fayez’s abaya. Underneath, he was wearing a green shirt and black trousers.

They immediately began to beat him with wooden rods. The first few blows broke his arm, which dangled limply by his side, said Adam. She managed to grab the boy away from the militiamen, but they quickly snatched him back. They ordered him to crawl on the ground and kept striking him. Adam watched as they beat Fayez to death, smashing his head.

“The last words I heard were Fayez shouting, ‘Mama leave,’” she said. Her son, she said, had been trying to protect her. Next to his body lay two other young Masalit men in their 20s, Adam said. She had watched as they too were clubbed to death.

Adam had raised Fayez from the age of 3, when his mother, her sister-in-law, died. “He used to bring the girls biscuits and sweets,” she recalled. “He would sit on the mat and say to the girls: Whoever gives me a kiss on the cheek, gets a biscuit.” LOSING THE LAND

Abdullah, the Sudanese soldier who described the child killings, had been in the army for nine years until he fled. He said he joined the military because of the history of attacks on his people. A Masalit from West Darfur, he said some of his earliest memories are of being attacked because of his ethnicity. He recalls being targeted by Arab militias as far back as the 1990s, when he was eight years old and his family was attacked in their village near El Geneina. Militiamen on horseback stormed the village, looting it and setting it on fire, he said. His family fled.

“They used to call us slaves. There was no government to protect us,” he said, interviewed in a hospital in Adre, where he was getting treatment last month for his injured hand. “I joined the army to protect my people.” West Darfur is the historic homeland of the Masalit. They claim ownership of an area that includes both the Sudanese state of West Darfur and eastern Chad. It is known as “Dar Masalit,” meaning home of the Masalit. In the late 19th century, the Masalit, who traditionally were farmers, established a sultanate in the area.

The history of Dar Masalit is punctuated with conflict. In the early 20th century, for instance, the tribe fought the advance of French colonizers. The current sultan of the Masalit, Saad Bahreldin, told Reuters in an interview that the Masalit spread false rumors that the tribe’s fighters were cannibals. That made the French soldiers “fearful of the Masalit,” he said. The sultans’ powers, prominent Masalit say, included collecting levies from farmers during harvest time and mediating tribal disputes. They also allocated land to other tribes to live and work on, while maintaining ownership.

In the 1990s, however, the government of President Omar al-Bashir, like its predecessors, led a campaign to Arabize Sudan as a way of cementing its hold on power. It engineered demographic changes by dividing the land between multiple tribes – a move that weakened the power of the sultan. Among them were Arab nomads who migrated from Chad during times of famine and settled in West Darfur, fueling competition over scarce resources like land and water, which spurred conflict. During Bashir’s decades-long autocratic rule, Arab militias armed by the government attacked the non-Arab residents of Darfur, killing them and burning their homes. Through the late 1990s and into the early 2000s, groups like Masalit farmers were uprooted from their lands.

In response, rebel groups – mostly from the marginalized non-Arab tribes like the Masalit, Fur and Zaghawa – rose up against Bashir in 2003. Bashir retaliated by unleashing the Arab militias known as the Janjaweed on the inhabitants of Darfur. The violence led to the deaths of an estimated 300,000 people by 2008, many from starvation. The RSF was born out of the Janjaweed. The International Criminal Court subsequently charged Bashir with crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide, and issued two warrants for his arrest. Sudan hasn’t extradited Bashir. Because the ICC only tries suspects who are physically present at the court, his case remains in the pre-trial phase. Bashir has said that his government was putting down a rebellion and he has denied the ICC charges, calling them politically motivated.

Bashir was overthrown in a popular uprising in 2019. Before the war started, he was moved from prison to a military hospital. His current whereabouts are unknown, and he could not be reached for comment. The violence in the early 2000s and subsequent sporadic attacks on the Masalit by Arab militias drove large numbers of the tribe into camps for internally displaced people, many of them in El Geneina. These camps were attacked this year by the RSF and its allies.

“The goal is to impoverish the nation, starve the people, displace them, and kill them,” said Bahreldin, the Masalit sultan, referring to his tribe. He spoke to Reuters in the Chadian capital of N’Djamena, where he fled amid the assault on El Geneina in June. “This is a premeditated action” by the RSF and Arab militias, he said. “A genocide of the Masalit.”

Melanie O’Brien, a visiting professor at the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at the University of Minnesota, believes there “is enough to call it genocide.” The intent, she adds, is clear: “To destroy the Masalit, at least in part.” The targeting of adult Masalit men, O’Brien said, could be equated with the Serbian massacre of Bosnian Muslim boys and men of military age at Srebrenica in 1995. “The courts held that was genocide, because it was a targeting of the male population of the Bosnian Muslims,” she said. “I would argue that the same thing applies here.”

Winning genocide convictions, however, is difficult, say international law experts. That's because prosecutors must prove suspects acted with intent to destroy a group in whole or part – a high hurdle. FAMILIES WITHOUT FATHERS

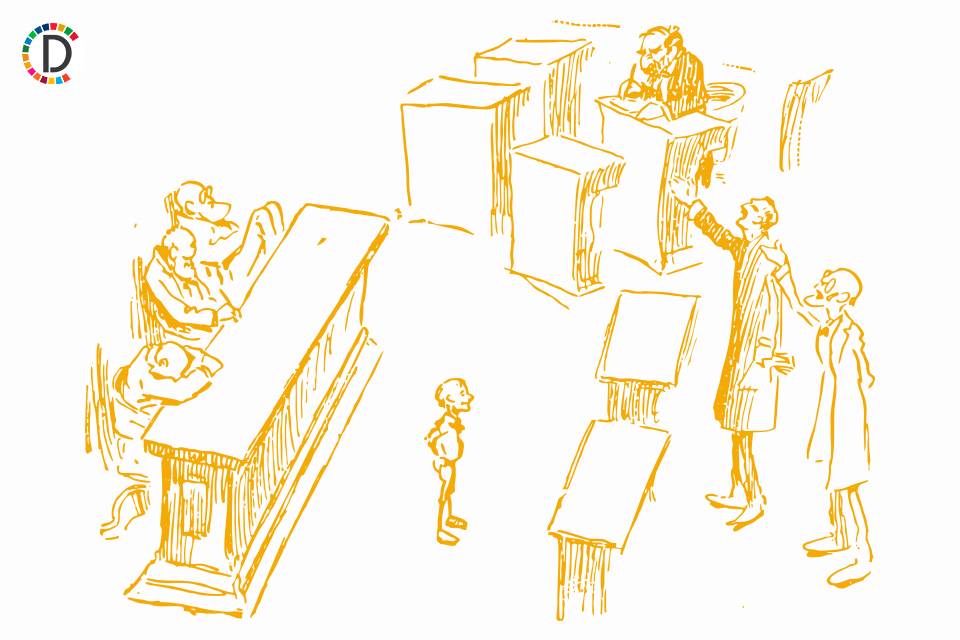

One day in mid-November, at the request of Reuters, a Masalit community leader drove through Ourang, one of the refugee camps on the Chad side of the border with Sudan, making an announcement through a loudspeaker – the main means of mass communication in the camp. There is almost no mobile phone coverage in Ourang. The community leader called upon women whose children had been killed in the El Geneina violence to meet the following day under a large neem tree to tell their stories. The next day, by 9 a.m., dozens of women had gathered under the tree. Throughout the day, more continued to come.

Many said they had lost children. Others said they came because members of their families, mostly men – husbands, brothers, fathers – had been killed or were missing. One woman said her 16-year-old son, her father and her brother were all killed in April by RSF forces – gunned down in a neighbor’s home where they had tried to hide.

A second woman said Arab militiamen descended on a school in a displaced persons camp in El Geneina, also in April, and opened fire on a group of men there, killing her father and one of her brothers. The next day, she said, they killed another of her brothers. A third woman described how four of her uncles were gunned down in the family home in Ardamata in early November. Her husband, a soldier in the Sudanese army, has been missing since then, she said.

Gamal Abdel Rahman, the Ourang community leader, estimated that 70% of the people in the camp are women and children. According to the U.N. figures, in Ourang there are almost twice as many women as men in the 18-59 age category – 10,500 females and 5,300 males. In videos posted on social media during and after the November violence in El Geneina, dozens of Masalit boys and men are shown being detained at locations in and around the city. Reuters has verified some of these videos.

At least two of the videos show groups of men being forced by fighters in RSF uniforms and Arab militiamen to walk and run through fields in the direction of the airport in El Geneina. Eyewitnesses have told Reuters that captives were tortured and executed at the airport. Another video, previously reported by Reuters, shows a group of men being held by armed fighters on a bridge in El Geneina and whipped. In the first wave of violence in the city, between April and June, many Masalit men said they left their wives and children and went into hiding to protect themselves and their families, knowing that the RSF and Arab militias were seeking out men. Some hid in ethnically mixed neighborhoods, while others took refuge in the Ardamata district near the Sudanese army base, only to be targeted again in the renewed attacks in November. Some said they managed to get to Chad by bribing Arabs along the way for help or paying Arab drivers to smuggle them through checkpoints manned by militiamen.

In some families, all the men were killed. Huda Ibrahim Ismail said she and her two teenage sons were with her husband when he was killed in El Geneina on June 15, after RSF forces and Arab militiamen opened fire on a group of people in the city. Hours later, she and her two sons were part of a crowd that came under attack again by the RSF and Arab fighters.

As they fled the attack, Ismail said, her sons, Rasheed, 19, and Sherif, 17, were approached by a car carrying men in RSF uniform. The boys made a run for it. The RSF men spotted them and gave chase. Ismail said she then watched as her sons were tied up and executed with gunshots to the head. “I am on my own now,” she said. “I have no one.”

(This story has not been edited by Devdiscourse staff and is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)